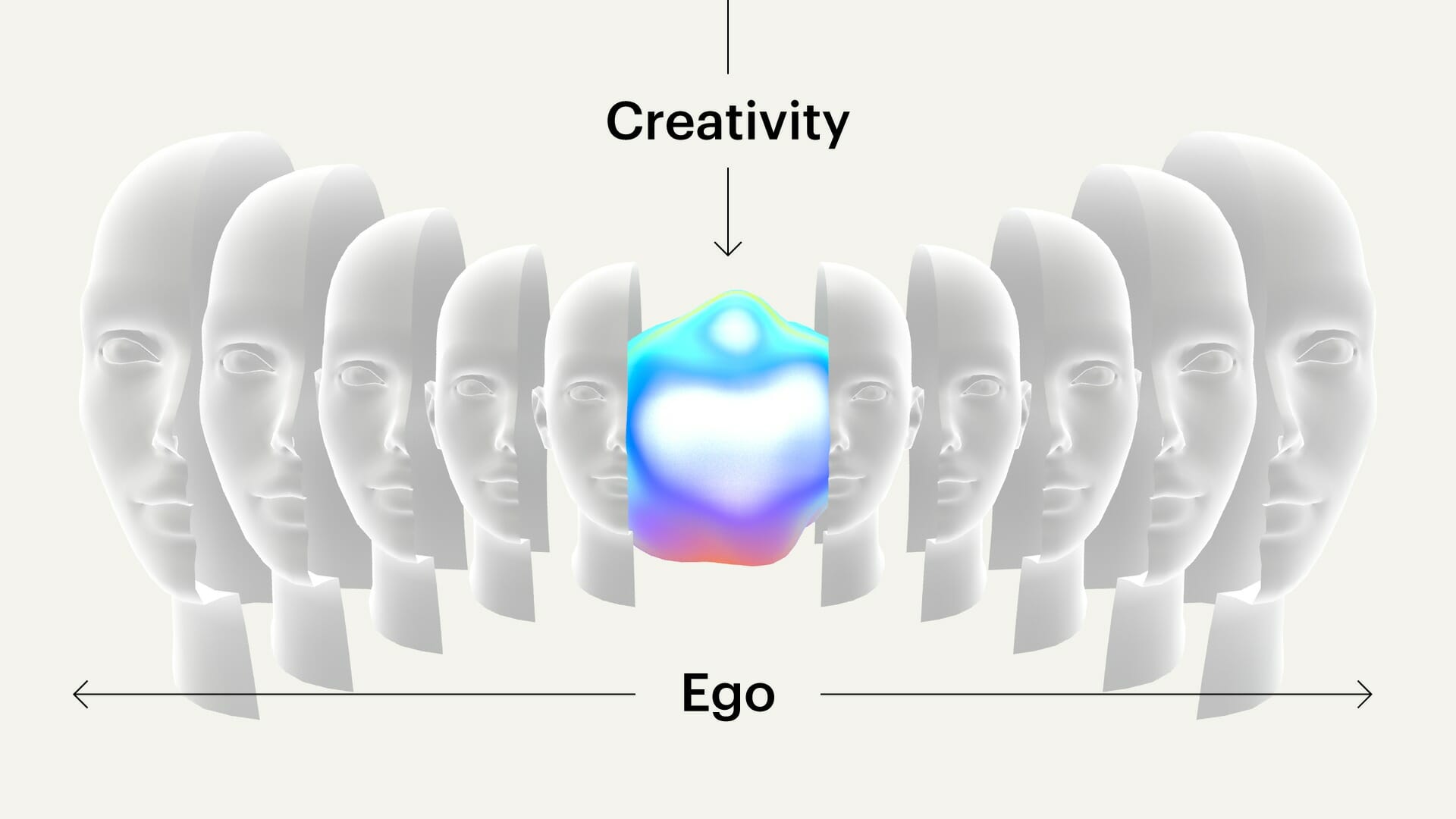

As creatives, we believe deeply in our craft and put ourselves fully into what we make. Our humor, our creativity, our problem-solving gets baked into the product. So, when work is rejected, it can feel like you’re being rejected. Add tight deadlines and multiple projects to the mix, and emotions are even higher. The key to keeping a level head is all about leaving your ego at the door and keeping a healthy authorial distance between maker and product. This is a guide for designers of all skill levels, clients, strategists—anyone taking part in the design process.

Assume Good

If someone suggests changing the design, assume that they are coming from a good place. They want to improve the work and giving them the benefit of the doubt will not only start the collaboration off on the right foot, but it’ll also build trust over time.

Try it on for Size

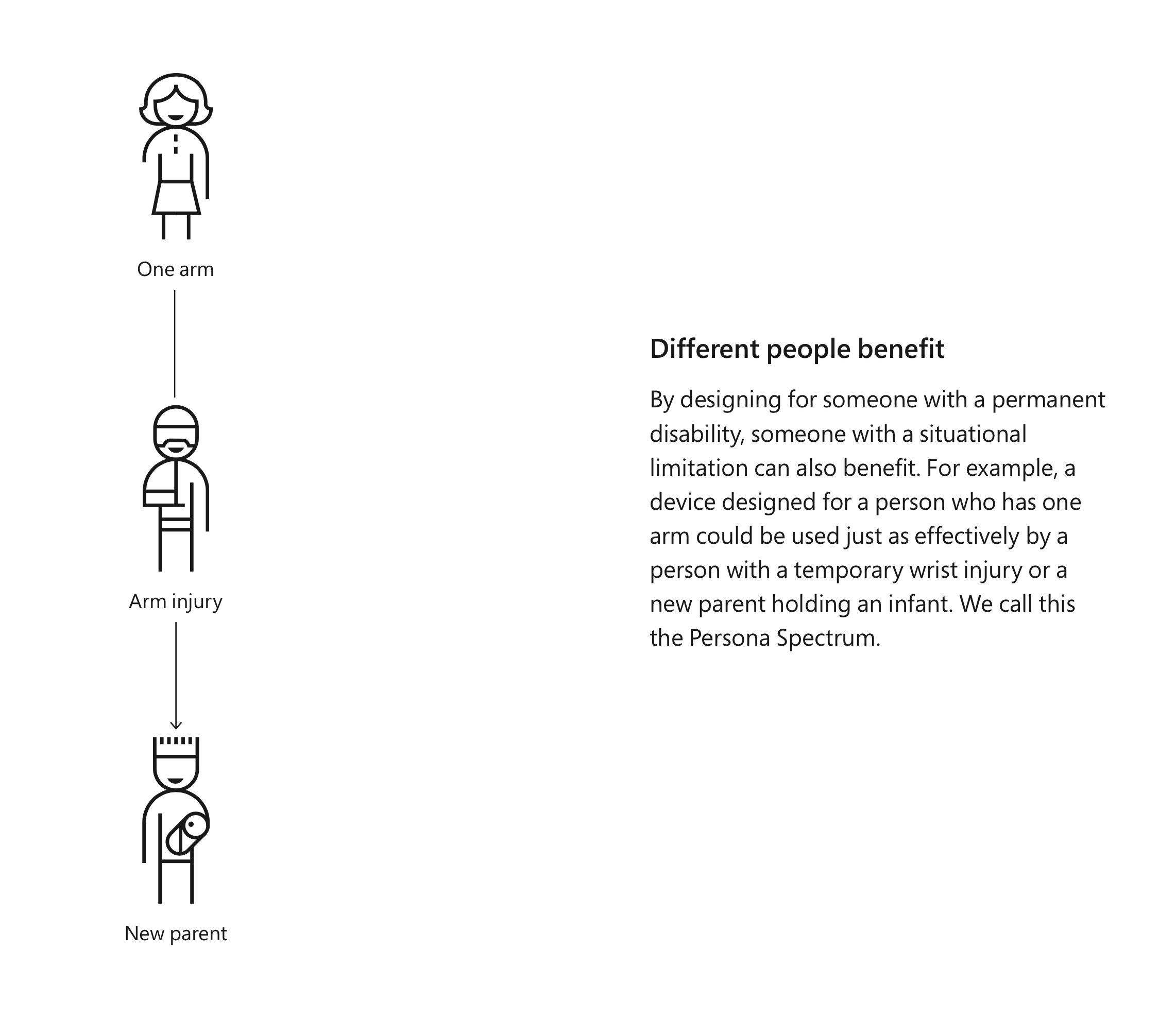

If you disagree with a piece of feedback, implement it anyway and see if it works. Your initial assumptions could either be totally wrong, or it could spur some additional inspiration that you wouldn’t have come to otherwise. The important part of this is to actually try and be an advocate for the thing that you may have initially disagreed with. If you can design from their viewpoint, you might uncover the root cause of the piece of feedback and be able to address it better.

Yes and…

If you’re collaborating with someone and they mention an idea, try to build on their idea even just a little bit. They have given you a nugget and you can help them shine it into something amazing. It takes a lot of courage to share ideas. If you have made a safe environment to share thoughts, you’ll uncover gems that otherwise would be kept secret.

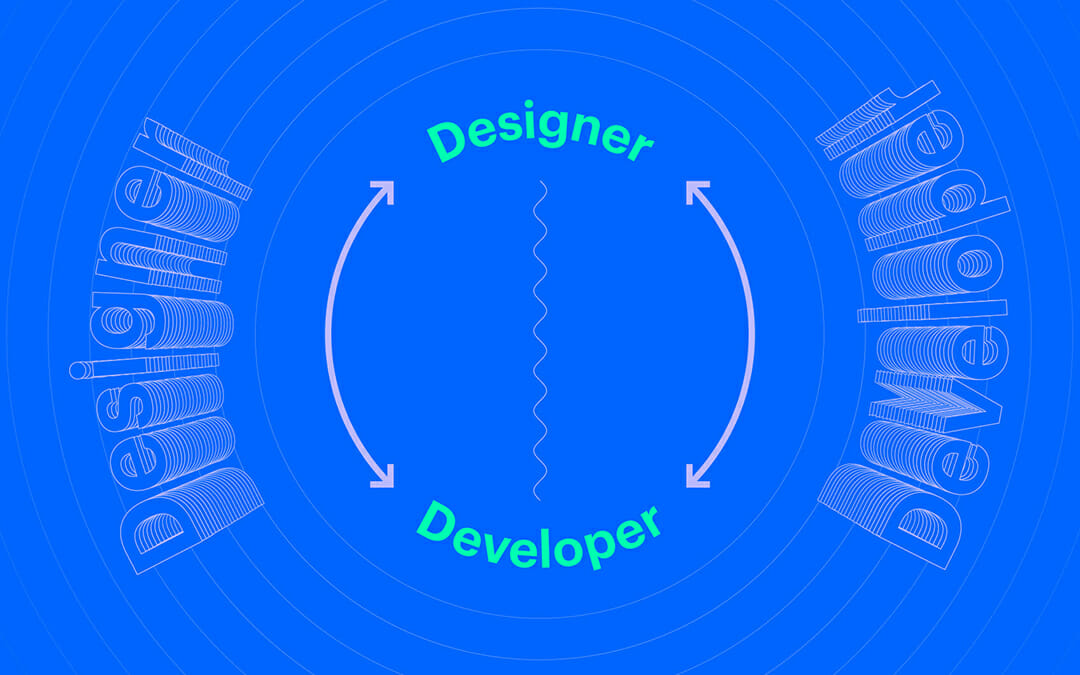

It’s Not YOUR Design, It’s THE Design

Remember that no matter what, everyone’s job is to work together on the design. It is not your solo creation to be hung in a museum long after you’re dead. It’s a communal work that is being refined by multiple people. This helps distance yourself from any feedback that might sting. Oftentimes, when people are criticizing a piece of work, they are trying to improve the work—not make you look bad.

Liven Up the Mood

Even if you feel very attached to a design you’ve been working on and someone points out a flaw, use that as an opportunity for humor. Oftentimes, if you can shift your perspective to the person who criticized the design, you can find a joke to make about it. Humor doesn’t just lighten the mood and facilitate good collaboration, humor has a sneaky way of lowering our own defenses and opening our minds to new ideas. Many brilliant ideas start out as “joke ideas,” something we throw out impulsively, wildly, provocatively. People don’t judge them with the same mind frame because “it’s just a joke.” And this type of playful ideation makes “joke ideas” become real ideas, with real impact.

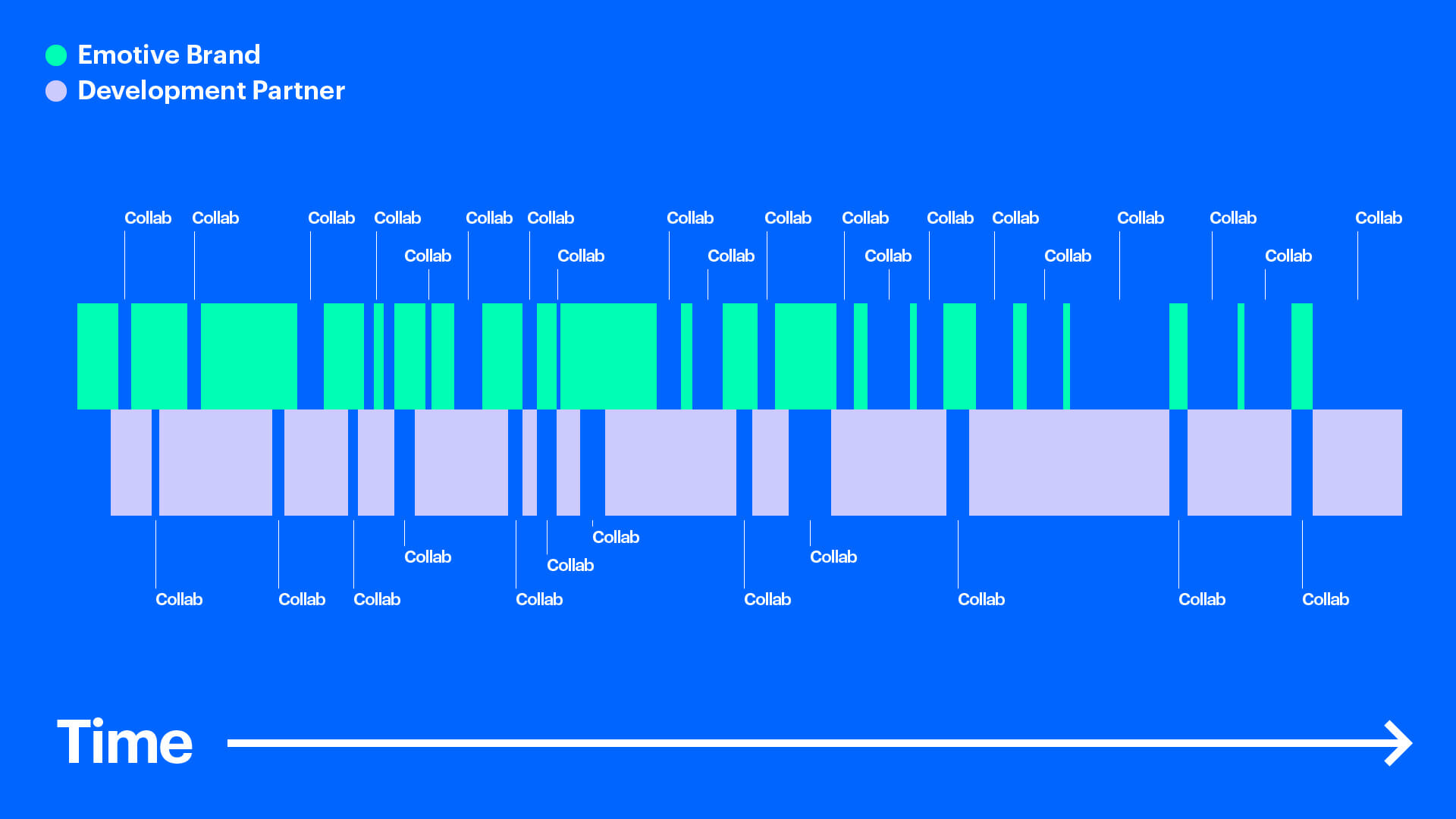

How it Happens in Practice

Imagine you have an internal design review in 2 days—this time around everyone is expecting the work to be fully designed. Strategy will be there, client services, project management, and the managing director might stroll by. But your designs are stuck, you can’t seem to push through. Instead of trying to break through that wall on your own, take initiative and reach out to someone. Ask them how they’d make it cooler (instead of asking for their feedback). This starts the conversation off as immediately collaborative and frames it so that what they suggest is already going to be an improvement. When they think of something, get stoked about it. Really, let yourself feel that emotion. Then execute their suggestion. It may feel like you’re going down the wrong path, but it’s an open door that will let you get through that wall that was blocking you before.

5 Quick Tips:

- Get fast. If it only takes you 20 minutes to make changes, it won’t be that big of a deal. But if it takes 2 hours, then feedback hurts because you know you’re staying late.

- Meditate. 10 minutes a day, focus on your breath. This trains the brain to stay calm in situations that are overwhelming.

- Write it down. If you don’t, you’ll forget it and you won’t do it.

- Be proactive. Ask for feedback. You’ll become accustomed to receiving it gracefully.

- Practice. The goal here isn’t to be perfect. In fact, it’s the opposite. Shedding your ego is an ongoing practice that takes regular maintenance. Shedding your ego doesn’t need to be an earth-shattering event. It can be a series of small moments that are strung together.

Emotive Brand is a brand strategy and design agency in Oakland, California.